Powders as food, not magic

Protein powders sit in an awkward space between supplement and food. On paper they are simply concentrated milk or plant proteins, filtered and dried into a form that mixes quickly with water or milk. In marketing material they often sound more like performance upgrades than ingredients. The truth is less dramatic and arguably more useful.

If your current diet already includes regular portions of lean meat, fish, eggs, dairy, beans and lentils, you may not need a tub of powder to hit sensible targets.[2] For some people, though, a shake acts as a reliable back‑up plan. It can help when appetite is low, when you are travelling, or when work makes regular cooking awkward.

How much can you realistically get from food?

Start by looking at what a day of higher‑protein eating through ordinary food might include:

- Breakfast: Greek yoghurt (150 g) with oats and fruit – roughly 20–25 g of protein.

- Lunch: sandwich or wrap filled with chicken, tofu or beans – another 20–30 g.

- Evening meal: a palm‑sized portion of meat, fish or plant protein – 25–35 g.

Without any supplements you may already be sitting at 65–80 g of protein, and more if snacks include nuts, milk or cheese. For many people with moderate training loads this is entirely adequate. Where powder comes in is when you:

- Struggle to eat enough due to low appetite or busy schedules.

- Follow a vegetarian or vegan diet and want convenient options.

- Are deliberately pushing for higher intakes during heavy training blocks.

Looking at common supplement categories

Among gym‑goers a handful of products appear again and again. They differ in evidence quality and relevance, but the broad picture is:

| Supplement | Evidence snapshot | Typical context |

|---|---|---|

| Whey or plant protein | Well‑studied for convenience; supports daily protein intake. | Busy schedules, post‑training snacks, higher‑protein breakfasts. |

| Creatine monohydrate | Strong evidence for power and strength in many studies.[1] | Repeated high‑intensity efforts, resistance training blocks. |

| Caffeine | Well‑studied for alertness and perceived exertion. | Endurance events, demanding sessions, early‑morning training. |

| Branched‑chain amino acids (BCAAs) | Mixed evidence if total protein is already high. | Niche use; often unnecessary when protein intake is adequate. |

Examples of powders used in the real world

On Protein Pitstop we often talk in concrete examples rather than abstract categories. Below are two familiar powders that illustrate different approaches.

Two contrasting protein powders

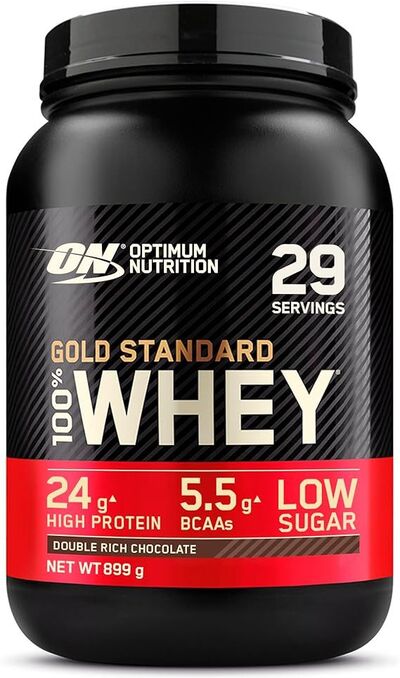

Gold Standard Whey

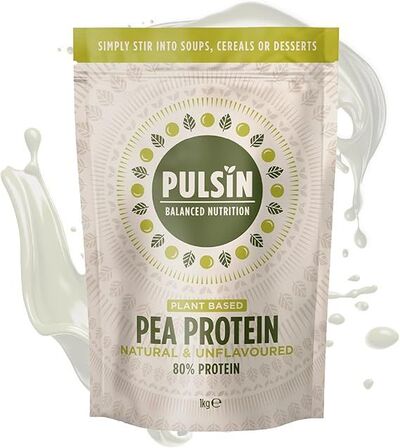

Pea Protein Powder

Questions to ask before you buy

Instead of starting with the supplement aisle, start with a short audit:

- Am I already covering basic nutrition—regular meals, fruit, vegetables and enough total protein?

- Is there a specific problem I hope a supplement will solve (time, appetite, recovery, ethics, budget)?

- Have I checked whether the product has been independently tested or certified?

If you cannot answer those questions, pause before adding another tub to your cupboard. In many cases, improving sleep, planning food shopping or adding a simple snack will have more impact than a complicated “stack”.

Putting powders in their place

A practical way to think about protein powder is as a bridge between where you are and where you want your intake to be. It should not crowd out whole foods that bring fibre, vitamins, minerals and enjoyment. When used with a clear purpose—such as topping up protein at breakfast or supporting recovery after heavy training—it can be a helpful part of the toolkit.

When tubs start piling up and flavours sit half‑used at the back of the cupboard, it is a sign the balance has tipped too far. At that point, revisiting your routine and simplifying may save money and effort.

References

Choosing a Powder with Purpose

When you are ready to buy, our round‑ups narrow the field to powders that balance taste, value and clear labelling.

Top Whey Powders Top Vegan Powders